I can cross another one off the long list of mill sites to see in the Ozarks. A few weeks ago, my family and I visited Bollinger Mill in Cape Girardeau County. Having traipsed up, down and all-around in several mills, I have come to the conclusion that the main reason mills are so appealing to the general public is because they tell a story, almost soap-operatic in nature, of bygone days. Without the history of the people who built and operated and used the mill, the site would just be another building on a creek or river in Missouri.

Mills come with long histories—often of arson, of romance (Remember the mail-order bride at Dawt Mill?), of danger—or sometimes, of man’s weaknesses, such as alcohol abuse, loneliness, and selfishness. Mills served as social centers for late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century culture, and farmers brought their corn and their families to this mill from as far away as 100 miles away. By the 1940s, most mill operations in the country had folded.

The Bollinger Mill touts a colorful history, too. In 1797, a North Carolinian transplant named George Frederick Bollinger received a land grant from Don Louis Lorimier, the Spanish commandant in Cape Girardeau. In exchange for the 640 acres, Bollinger agreed to recruit more Carolinians to the area.

In 1800 he returned with 20 more families. Of course, it helped that six of the men were his brothers. After recruiting workers, Bollinger began the arduous task of building the first mill. Notice the “first” part. Most mills are not original. Few have survived without being burned or flooded out, and this mill is no exception.

Bollinger became successful quickly. In 1812, he was elected to be a member of the first territorial assembly, which met in St. Louis. He served in four sessions, until Missouri achieved statehood in 1821. It was natural that Bollinger would become a state senator, and he was one of the first senators to meet at the Old State Capitol in St. Charles. He participated in the Electoral College that placed Andrew Jackson in the highest office in the land in 1832.

Between legislative sessions Bollinger stayed busy improving the mill. He replaced the lower foundation of the mill and the dam with limestone in 1825. Teams of oxen hauled the massive blocks, which are still there today, to the mill from a nearby quarry. When Bollinger died, his daughter, Sarah, inherited the mill and ran it into the ground, along with the help of her two sons. During the Civil War, because they disapproved of Sarah’s Southern sympathies and wanted to prevent the mill from supplying grain to the Confederacy, Union troops burned the mill’s top floors.

In 1866, out of necessity Sarah sold the mill to Solomon R. Burford, who rebuilt the top structure. For this task, he chose bricks and stone. The workmen finally stopped building when they reached the fourth story. Sometime during Burford’s ownership, the mill’s power system changed from water wheel to turbine. The village around the mill site was named Burfordville and its post office still stands.

The mill operated until 1948. In 1953, a descendent of the Bollinger family bought the mill and gave it to the local historical society, who then gave it to the state in 1967. The Department of Natural Resources took the site, researched its history and created an impressive interpretive center within the old brick walls. Tours of the site often include the chance to see cornmeal ground between original buhr stones.

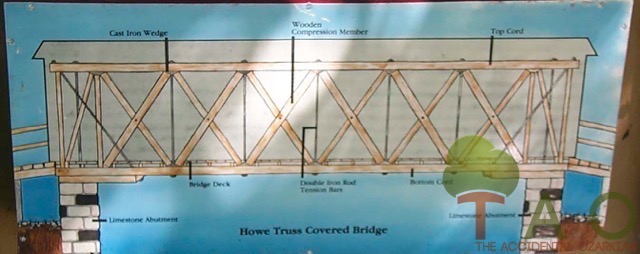

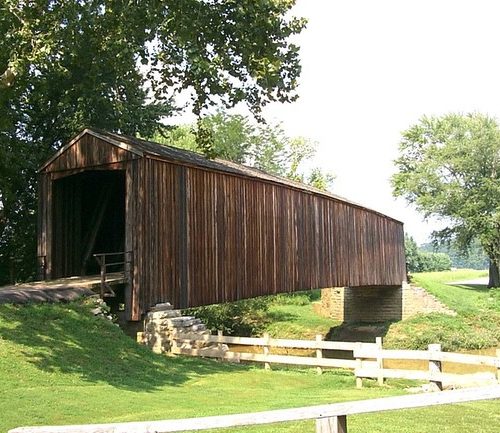

The land around the mill has 14 picnic sties and a short hiking trail to the Burford family cemetery. Massive oak trees provide plenty of shade, and amateur photographers will delight in the possibilities for good quality photographs. There is also a covered bridge alongside the mill. But, that, is another column.

I would like to return to this area in the fall, when the colors peak. If you want to see Bollinger Mill, travel southwest toward Cape Girardeau. The park is located off Highway 34, just outside of the city. For more information, call 573-243-4591.

Check the website for hours according to seasons, directions and lovely photographs: https://mostateparks.com/park/bollinger-mill-state-historic-site

This installment of “The Accidental Ozarkian” was first published in the St. James Leader-Journal on Sept 03, 2001.