“Help me … I just want to be loved.” Lines of zigzag embroidery filled a cloth sheet that hung on the wall at the Glore Psychiatric Museum (named after George Glore, founder) in St. Joseph, Mo. A shudder ran down my spine as I recognized wedding vows and lines from songs stitched haphazardly in multiple colors and sizes.

The schizophrenic woman who sewed this creation was just one of the thousands of former occupants once housed in the State Lunatic Asylum No. 2. The museum stands today, possibly the best of its genre in the nation, to educate people on the history of mental illness and to impress upon people that mental illness can be treated humanely.

The original hospital has been refurbished and operates as a state prison. It stands a stone’s throw away from the museum, behind a tall, barbed fence.

The State Lunatic Asylum No. 2 opened its doors to 25 patients on November 9, 1874. It had a 275-bed capacity, but grew to hold nearly 3,000 patients by the 1950s. The name changed in 1899 to St. Joseph State Hospital.

Families with nowhere else to turn committed their loved ones to the asylum, and were instructed to drop off a nice set of clothing with the patient – for burial. According to information near the morgue in the basement of the museum, some families never returned to visit their relatives.

Rife with memorabilia from the old days and old ways, the museum included furniture, a grand staircase and photographs. The tools of trade, though, caught my interest – the instruments used for bleeding, dousing, stomping, restraining, and spinning. The instruments for performing lobotomies lay in a glass case, alongside the details of the procedure.

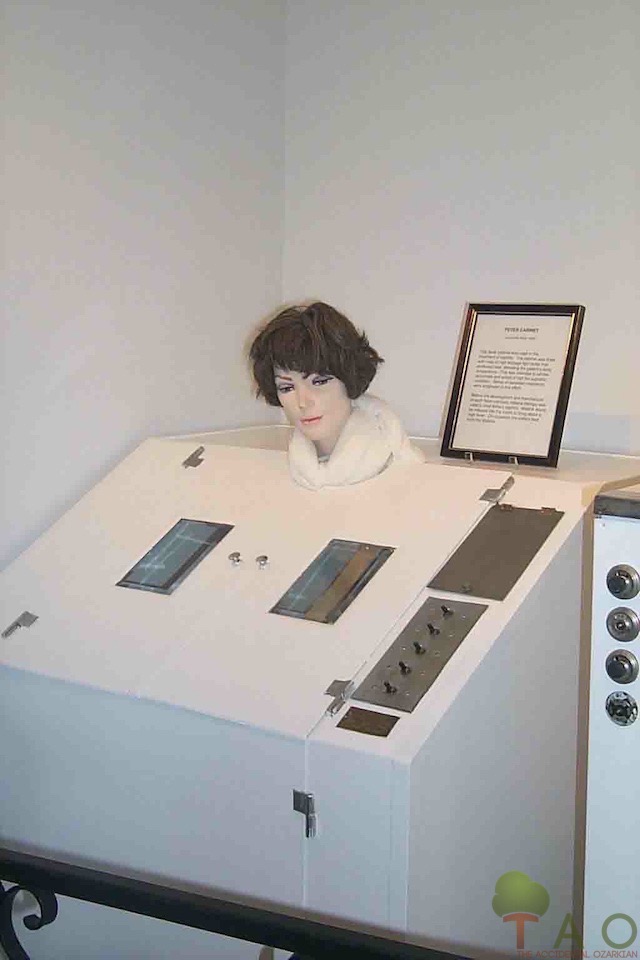

Fever cabinets, a product of early 20th century reasoning, were used to treat syphilitic patients. Mannequins lay and sat in some of the early devices and restraints, created by folks who might have “taken a walk on the dark side” themselves, or so it seems.

Benjamin Rush, known as “The Father of American Psychiatry,” and also as a signer of the Declaration of Independence, built the tranquilizer chair. An actual tranquilizer chair, complete with a boxed-in area for the head, stood on display. Another of Rush’s tools, a replica of his knife used for bleeding patients to release evil spirits, was also on display.

The “Bath of Surprise” consisted of a platform with a drop-floor that sent the patient into a vat of icy water. Some patients didn’t survive the shock. The model of O’Halloran’s Swing did not leave much to the imagination. This piece of equipment looked like it belonged in an old-time carnival, where a patient was strapped in and then set in circular motion up to 100 RPMs.

The museum’s four floors held fascinating dioramas and actual recreations of the types of rooms once used. A glass frame housed an interesting exhibit. In 1929 a female patient complained of stomach pain. When they opened her up, the doctors found 1446 foreign items in her intestines and stomach – 453 nails, screws, safety pins, spoon tops, buttons and other assorted items. She died during the operation.

Two other displays deserve description. A patient had written and stuffed 525 notes into the back of a television set. The notes answered his questions from multiple therapy sessions, and the television and a bulletin board full of the notes stood on display next to the cage of cigarette wrappers. It held 100,000 cigarette wrappers that a smoker saved because he imagined a redemption program by the cigarette companies for a wheelchair. (When one of the companies found out about the patient’s quest, it donated the funds for a wheelchair.)

Artwork from the patients throughout the years also adorned the walls, and a display that focused on children explained the educational programs of the Woodson Children’s Psychiatric Hospital. Youngsters participated in restoring two cars and these were on display, too. The public school district now uses the nearby building.

The gift shop held some eccentric items – gummy (candy) brains, rubberized brains to squeeze and, of course, tee shirts with the name of the place on the front.

The new state hospital for the mentally ill sits across the street from the old location, and boasts a return rate, after a rehabilitation program, of 21 percent, as opposed to 58 percent in the 1950s and a much higher percentage at the turn of the last century.

First published Sept 19,2004.

Learn more about the Glore Psychiatric Museum.

Note: Some of the exhibits are not appropriate for young children to see.