Topaz Mill stands in a holler in Douglas County, a perfect representation of what a gristmill should look like, complete with a gushing spring nearby and a raceway. Next door to the mill stands an associated general store.

Neither of these buildings would be here had it not been for the energy and foresight of Joe O’Neal. Joe’s nephew, Joe Bob O’Neal, who lives onsite now, said his uncle bought this place in 1957. “When they bought this place, both of the buildings were in bad shape,” he recalled. “The siding was falling off and there wasn’t any glass in any of the windows and when my uncle had time and money, he got them closed in to keep the weather and varmints out.”

Joe Bob added that his aunt tried to get his uncle to burn down the mill. Little by little, year by year, Joe Bob’s uncle repaired and shored up the mill and general store, and even added paint to the store (which had never seen paint). Joe Bob spent some happy childhood days running on the grounds of this property, and now, a retired railroader, he loves to spend his time on a dirt bike on the 400-acre property.

You can read all about the general store and our tour through it, conducted by Joe Bob and Betsy, his wife. Now it’s time to look at the old mill.

Topaz Mill History

Topaz Mill is a place where my husband used to retreat to from high school days, playing hooky and swimming in the mill pond. About 18 miles south of Mountain Grove, the mill site is believed to have first been appreciated for its merits in about 1840, when Aaron and Alabeth Freeman settled near the spring and built the first grist mill.

According to “Water Mills of the Missouri Ozarks,” by George G. Suggs, Jr., the mill changed ownership several times between the deaths of the Freemans and its owner in 1890, Robert Hutcheson. Hutcheson and his wife, Mary, had great plans for the mill, and moved it farther from the spring, directing the water to energize the turbines via a dam and flume. In 1895, construction began on the three-story building that would grind not only flour, but also, corn.

Joe Bob reckoned that people painted mills red because red paint stays on longer, with its pigmentation. “My belief is that they came up with this dark red pigment, and realized that it protected the wood a lot better. That’s my thought on that.”

Modern Day Tour of Topaz Mill

“Everything is still in here!” said Joe Bob. “Everything! Here’s a copy of the receipt dated May 2, 1903 for $1650, which is $50 or $60,000.” The receipt included construction materials – such as chutes, rollers, scales and even blots – for the mill. “The goods for the mill were shipped on a train to Mountain Grove, and then somehow transported down to site by horse, oxen or mule,” added Joe Bob, who noted that oxen would have been the preferred method, since they are “stronger, tamer and you didn’t have to carry food for them because they could forage and take care of themselves.”

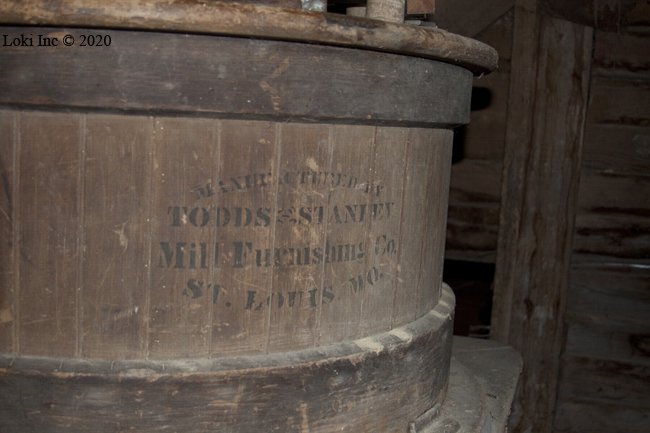

The equipment came from Great Western Manufacturing, out of Leavenworth, Kansas. This business still makes milling equipment today. You can see the company’s label and engraved metal lid on this piece of equipment in the mill.

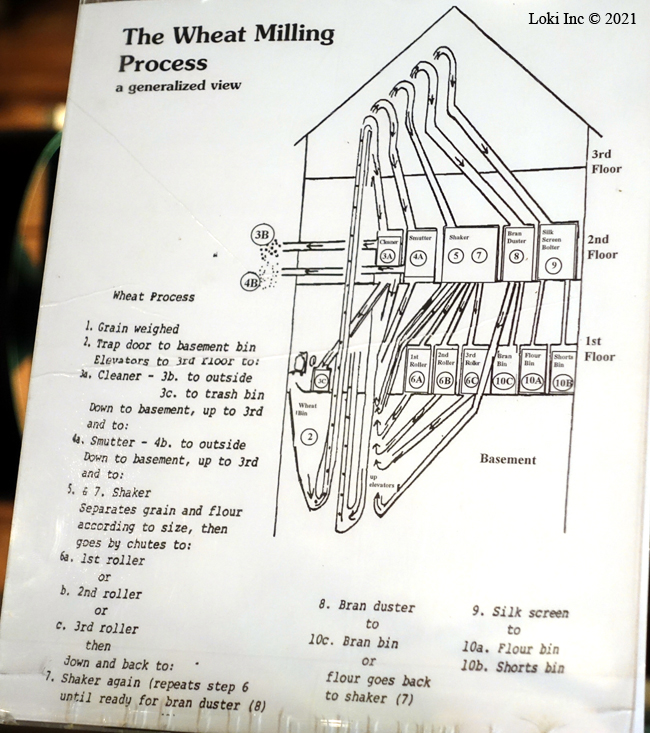

Joe Bob’s uncle ground corn and sold it for animal food, in the back room of the main floor. The grinding of the flour required a more intricate and complicated chuting system, which Joe Bob walked us through – meaning we had to take a trip upstairs.

(Jason Baird photo)

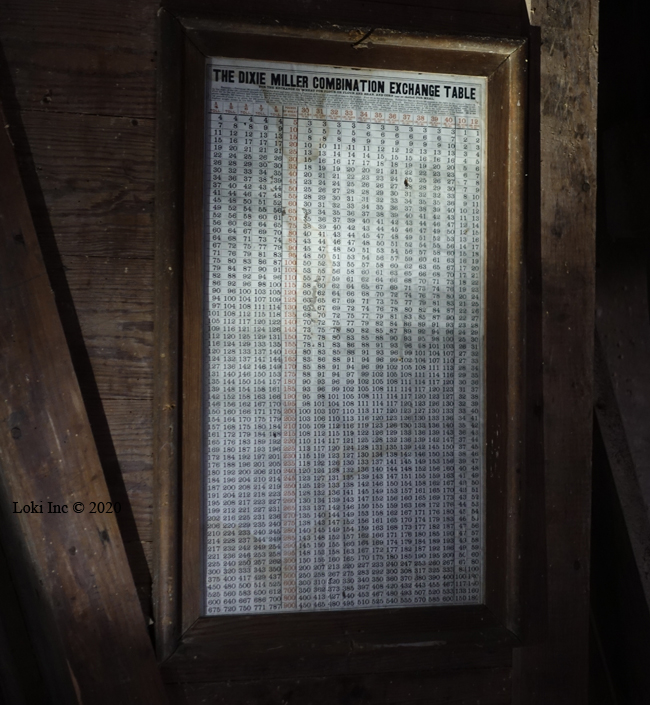

The Dixie Miller Combination Exchange Table

“That is a rare piece there,” said Joe Bob. There was a guy in here a few years ago who had been to mills all over country, who said he’d seen only two of these signs in existence. From SPOOM – Society for the Preservation of Old Mills – he explained it to me, and he might as well have been talking in French. It was so complicated I could not make heads or tails of it. If you bring so many pounds of corn or wheat in, you get this much and the miller gets this much.”

That big black tank is the smutter, which cleaned imperfections and smut from grain.

According to Joe Bob, “All you grind for refined flour is the endosperm, the white starchy stuff inside a grain of wheat. … Shorts were the germ and a little bran and a little bit of the endosperm that didn’t get separated out in the flour dressing machine. This was pig feed.”

“This was called a 4-barrel automatic mill, which meant it could process 40 barrels of flour a day, and I think a barrel is 196 pounds. The automatic part meant you dumped the wheat in the bin and you bagged the flour and the equipment did everything else,” explained Joe.

If you’re interested in the wheat milling process, here’s a general diagram from Alley Mill about the sequence. It helps to understand the chutes, pulleys and belts system a little more at Topaz Mill.

“These are roller mills, these are double rolls. With two chutes going in, it’s like two separate machines.”

The last place we explored once served the public as a local barber shop. The chair still stands in an alcove off to the side of the building. Haircuts cost 15 cents, according to lettering on a nearby wall.

At the end of the tour, Joe Bob said, “In a mill like this, when you kick that gear in, it all runs at once. You don’t turn one piece of equipment on or off. It all runs at the same time. The belts all have to be made exactly the right size. There’s no adjustment on a belt. … All your pulleys have a hump in the middle of them and that keeps the belt on them, but you’ve got to have them aligned just right.”

You can find out more about Topaz Mill on its Facebook page. Tours available through appointments, please.