You may have heard of “Ozark roadside tourist pottery,” birthed in the 1930s by Harold Horine, of Hollister, Missouri. The colorful swirly cement pots were Horine’s patented brainchild, and the story of how these interesting Ozarkian art pieces, renamed Mission Craft Pottery, wound up in the desert north of Phoenix led me to Sunnyslope, Arizona, last October.

Background on Ozark Roadside Tourist Pottery

First, though, it’s imperative to know more about the pottery that appeared on roadsides in the Ozarks during the Depression years. Horine worked as a plasterer and in his spare time, created a new type of pottery out of cement. In fact, it was so new, that in 1933 he saw his first patent realized. In 1936, the U.S. Patent Office granted him a second patent regarding the decorating of the clay pots and jars.

In a book titled “The Mission Craft Pottery Project, Sunnyslope, Arizona 1935 – 1939,” author Ed Dobbins writes that Horine called his business “Como Craft Pottery.” Horine and his mother ran the business, in their home located near the intersection of Highways 65 and 86 near Hollister. At that time, Dobbins writes, people visited the area in droves to see the “Shepherd of the Hills” country, made popular by the book of the same title in 1907, written by Harold Bell Wright. (If you haven’t read this book, you should. After a few chapters, you’ll begin to understand better the dialect of the people in this part of the country, too.)

Como Craft became wildly popular, and even appeared at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in the Missouri Building Exhibit. Indeed, I was mildly taken aback a few years ago to see a copy of “The National Geographic Magazine,” from May 1943, that featured the Ozarks, and in a photo section, a picture of Harold Horine swirling paint onto a jar. I saw this issue, along with the pottery at the Route 66 Museum in Lebanon, Missouri, which contains a small, but beautiful exhibit of Ozark roadside tourist pottery.

It’s interesting to note that Horine also sold what we might call “franchises.” Dobbins writes that buyers lived in Des Moines (Iowa), Mineral Wells (Texas), Latourell Falls (Oregon) and two unnamed sites in New Mexico. However, it is believed that Horine did not charge the Arizona location a fee of $500, like he did with the others.

Ozark Roadside Tourist Pottery, aka Desert Mission Pottery

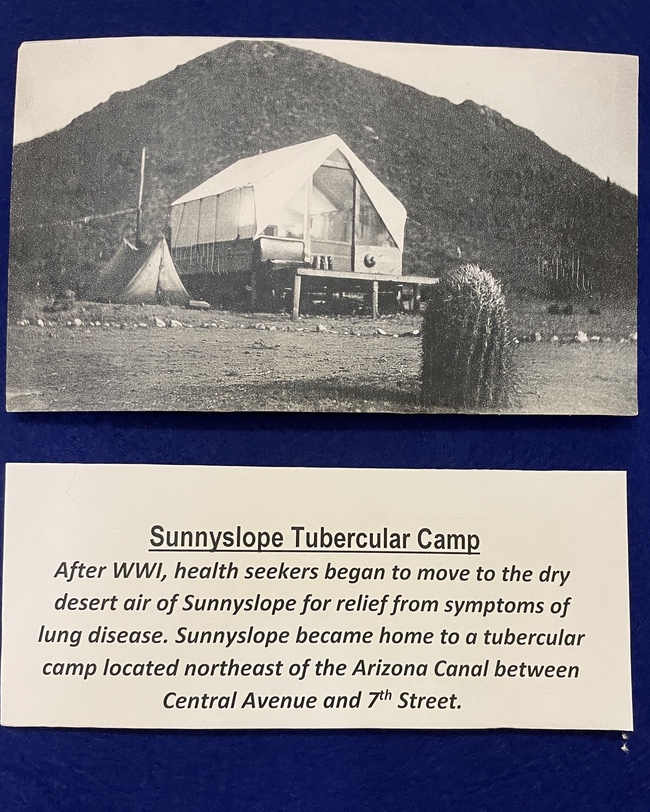

Dobbins writes, “It is likely that Horine offered to set up the pottery plant in Phoenix as a donation to the Mission.” The mission had evolved in the Sunnyslope area, which lies eight miles north of Phoenix, as a place that attracted people from around the country who suffered respiratory diseases and ailments, such as tuberculosis. Dobbins said that many WWI veterans traveled to this place to take advantage of the dry air. Dobbins also said there were several camps north of the canal in the Phoenix area during that time – known as a place to come to for health purposes. “It became known,” said Dobbins, “from 1911 to 1920, as a place that if you had no money and you were sick and you had nowhere to go, to come here and live it out.”

The Desert Mission opened its doors in 1925, and originated as a Presbyterian Sunday School. Rev. Joseph N. Hillhouse, who had worked as an Army photographer in WWI, led the effort to create this community onsite that ministered to people’s needs, especially the lowly and sick. As a result, Rev. Hillhouse needed to find funding for the outreach programs and other beneficial offerings. According to Dobbins, Rev. Hillhouse would advantage of a free passage service to ministers on railways, and travel east to raise money. In 1934, he found himself in southwest Missouri and met Horine. By January 1935, Rev. Hillhouse had the funds available for a pottery making plant, and in that same month, Horine and his mother arrived in Arizona and stayed for three weeks with Rev. Hilhouse. Horine trained the workers. Dobbins writes that both Horine and the reverend realized that not all the workers would be strong enough to lift some of the larger, heavier pots. So, the mission employed two men to do the heavy lifting.

They called this iteration of Horine’s idea Mission Craft pottery. The mission sold the pottery onsite, and a few places in Phoenix also carried some of the pottery. The pottery project lasted four years, until a new director replaced Rev. Hillhouse. The new director, Rev. Harvey Hood, thought the damp and dust-filled workplace was not conducive to the health and well-being of those people convalescing at the mission.

Dobbins suggests that the large inventory of leftover pots might also have been an indictor to the new director that it was time to move on to other endeavors. The Desert Mission continued to improve and expand, offering medical care and other services after the Reverends Hillhouse and Hood.

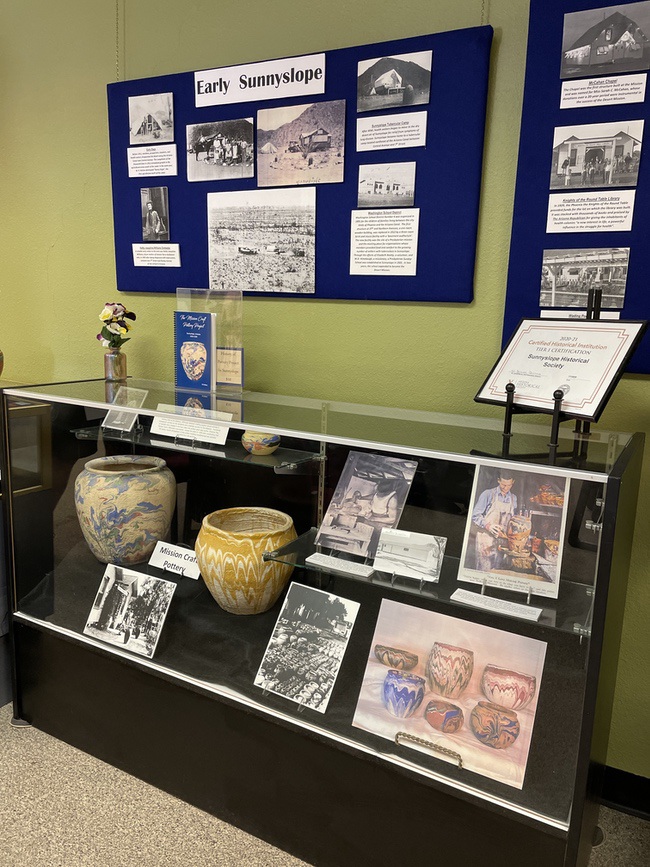

Sunnyslope Historical Society Museum

In early October, I traveled to Phoenix and met my sisters there. We drove up to Sunnyslope, to the Historical Society Museum, where we were met by Dave Smith, a volunteer at the museum, and the aforementioned author, Ed Dobbins. Dobbins, an avid pottery collector and retired audiologist, created the display featuring Mission Pottery onsite. The display features one piece of pottery that Dobbins knows was made by Horine.

Dobbins said, “I came here a few years ago when I was working on research for the area, and I figured I would come here to see what they had about the pottery and about the mission. The next thing you know, I was vice-president.”

Dobbins said the museum needed a new display. He said that first saw this type of pottery while looking for local, Phoenix antique items. An antique dealer pulled out a box of cement pottery and told Dobbins that the pottery had been made at a local mission.

Dobbins said, “There really wasn’t anything published on Mission Pottery, maybe one or two sentences in a book. I started doing the research on it. I was able to find the inventor’s son. … Frank Horine, over in New Mexico. He was one of several authors on a research paper published by Sandia Labs on using moths to detect explosives! I said, ‘That’s pretty weird, this guy that invented that pottery — maybe they’re related!’ I was the first person that ever contacted him about the pottery.”

Frank Horine was born in 1942, so according to Dobbins, he really didn’t see his father make the pottery, but he had heard about it. Horine gave Dobbins photos, which are in the book and in the museum.

Missouri Ozark Roadside Tourist Pottery

Horine closed Como Craft at the beginning of the US’s involvement in WWII. Others who paid for and learned the trade skills continued to make the pottery.

One of the major problems in identifying the original Mission Craft or Ozark roadside tourist pottery is that very few, if any, of the pieces have signatures of the potters.

I first saw it in an antiques mall up in Houston, Missouri, when my friend – herself a collector and a lover of antiques – pointed it out to me. Let’s just say, I was hooked. I like its history, and I am fond of the bright colors and sturdy qualities. The largest piece I’ve acquired is a bird bath ($12 at a flea market, which is truly a bargain) and the smallest is a tiny blue and white pot, about three inches across the top, which I use to hold my collection of gel pens.

I’m always on the lookout for this pottery, and scour boxes of pottery at auctions and yard sales, looking for that rare piece.

Dobbins said he thinks the colors are one of the main attractions to the pottery – “just the swirls and the combinations. It’s unusual.”

You can purchase Ozark Roadside tourist pottery at eBay, as well.