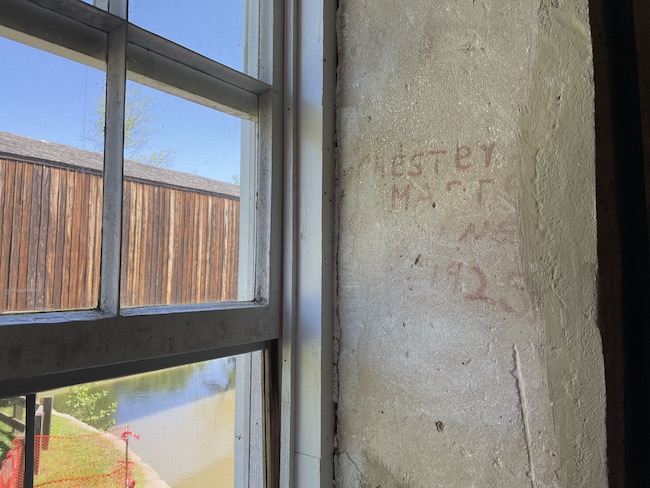

While onsite at the Bollinger Mill State Historic Site, near Cape Girardeau, Missouri, I noticed scrawls on the walls. When I asked Holly Rohr (DNR employee) about the autographed walls, she said, “We have lots of historic graffiti, both inside the mill and inside the covered bridge that dates from late 1800s to the early 1950s in the mill, and from the early 1900s in the bridge.”

Mill History

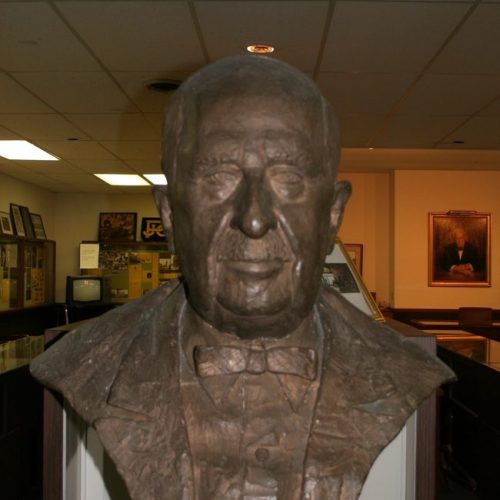

I’ve written about the mill earlier. History records that in 1797, a North Carolinian transplant named George Frederick Bollinger received a land grant from Don Louis Lorimier, the Spanish commandant in Cape Girardeau. In exchange for the 640 acres, Bollinger agreed to recruit more Carolinians to the area.

In 1800, he returned with 20 more families. Of course, it helped that six of the men were his brothers. After recruiting workers, Bollinger began the arduous task of building the first mill. Notice the “first” part. Most mills are not original. Few have survived without being burned or flooded out, and this mill is no exception.

Bollinger became successful quickly. In 1812, he was elected to be a member of the first territorial assembly, which met in St. Louis. He served in four sessions, until Missouri achieved statehood in 1821. It was natural that Bollinger would become a state senator, and he was one of the first senators to meet at the Old State Capitol in St. Charles. He participated in the Electoral College that placed Andrew Jackson in the highest office in the land in 1832.

Between legislative sessions Bollinger stayed busy improving the mill. He replaced the lower foundation of the mill and the dam with limestone in 1825. Teams of oxen hauled the massive blocks, which are still there today, to the mill from a nearby quarry. When Bollinger died, his daughter, Sarah, inherited the mill and ran it into the ground, along with the help of her two sons. During the Civil War, because they disapproved of Sarah’s Southern sympathies and wanted to prevent the mill from supplying grain to the Confederacy, Union troops burned the mill’s top floors.

In 1866, out of necessity Sarah sold the mill to Solomon R. Burford, who rebuilt the top structure. For this task, he chose bricks and stone. The workmen finally stopped building when they reached the fourth story. Sometime during Burford’s ownership, the mill’s power system changed from water wheel to turbine. The village around the mill site was named Burfordville and its post office still stands.

The mill operated until 1948. In 1953, a descendent of the Bollinger family bought the mill and gave it to the local historical society, who then gave it to the state in 1967. The Department of Natural Resources took the site, researched its history and created an impressive interpretive center within the old brick walls.

The land around the mill looks like a park, with picnic sites and a short hiking trail to the Burford family cemetery. Massive oak trees provide plenty of shade, and amateur photographers will delight in the possibilities for good quality photographs. There is also a covered bridge alongside the mill. But, that, is another column.

Bollinger Mill Graffiti

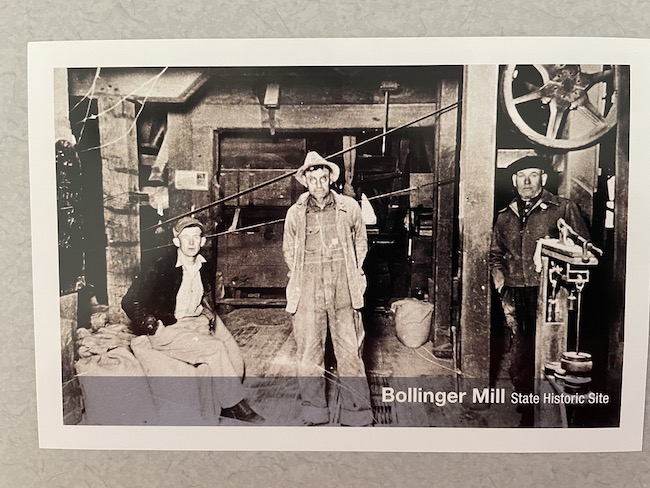

Holly said, “Graffiti inside the mill is mainly from millers and those who worked here. Fortunately, they put names and dates, so we know when they were there.” In fact, she mentioned a recent visit from Chester Masters’ granddaughter.

Masters is the man in the middle in the historic photo that is featured in a postcard from the mill. Master’s son also worked at the mill, along with five other men repairing the dam on the Whitewater River. All six men caught typhoid, and only three survived. Chester’s son did not.

Another family that visits annually is the McClard family. Their dad worked here around 1935. They usually stop by once a year because their father worked at the mill in 1935. He was an orphan from St. Louis and a local family adopted him, and he lived in Burfordville. His son, Mike, and his daughters stop by and look for his autograph on the elevator shaft.

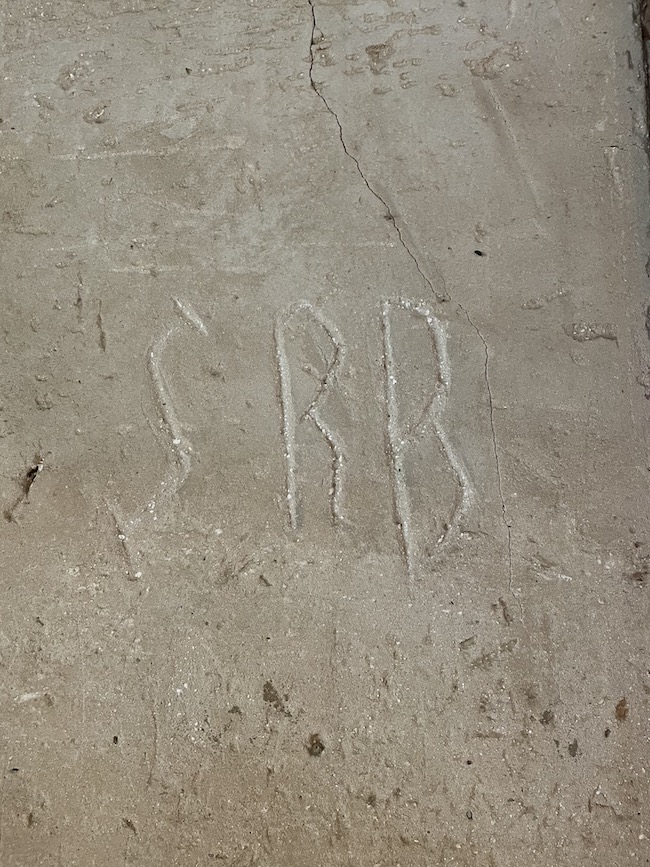

Hidden behind the door are the Solomon Richard Burford’s initials, SRB. He was the man who rebuilt the mill after the Civil War and the namesake of the community of Burfordville.

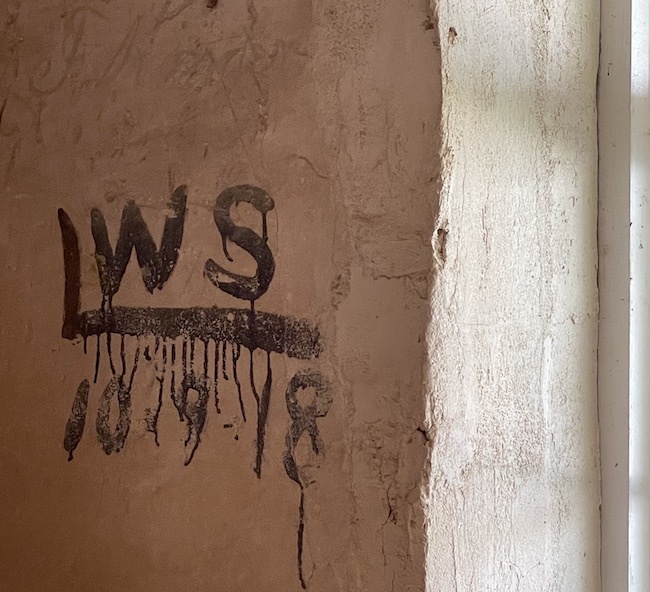

Holly continued, “All these stories are coming back to me. A lot of people look at this mark and think it’s a high water mark, but it’s actually L. W. Sutton. That’s how he did his Ls … he was one of the long-time employees of the mill. They brought him back here for the mill dedication in the 1960s. He was probably in his 80s by then, and he was one of the last few still around. His initials are here and they’re also on the front of the mill. It’s very faint, but you can see L.W. Sutton’s initials.”

If you want to see Bollinger Mill, travel toward Cape Girardeau. The park is located off Highway 34, just outside of the city. See the website for more information.