It’s a place I’ve wanted to see for a long time. It’s one of a kind, and holds the most comprehensive collection of WWI artifacts and memorabilia in the entire world. It’s just up the road from us here in the Ozarks, and if you don’t know much about WWI, or if you know a lot and want to learn even more, prepare to spend at least 3 hours onsite at this place — the National WWI Museum and Memorial. In fact, if you wanted to read everything on display here, it would probably take you 2 to 3 days.

Because of the wealth of items available, I chose a few to show you — along with history and stories — in this photo gallery.

The National WWI Museum and Memorial

The monument will make you pause, maybe even draw a deep breath. Two weeks after Armistice Day in 1918, leaders in Kansas City met to discuss the creation of an enduring monument to the men and women who served and died in the Great War. Architect H. Van Buren Magonigle designed the Liberty Memorial in the early 1920s. In 1995, Abend Singleton Associates not only restored the memorial, but also designed the museum under it. It is iconic, in that it has the memorial tower that reaches 217 feet above the courtyard, and below, Memory Hall — which holds tablets with the names of 441 Kansas Citians who gave their lives in the war. Also, in this area is the exhibit hall, or the main museum gallery. Flags from 22 Allied nations in the Great War stand arranged along the north and south walls, in the order that the countries entered.

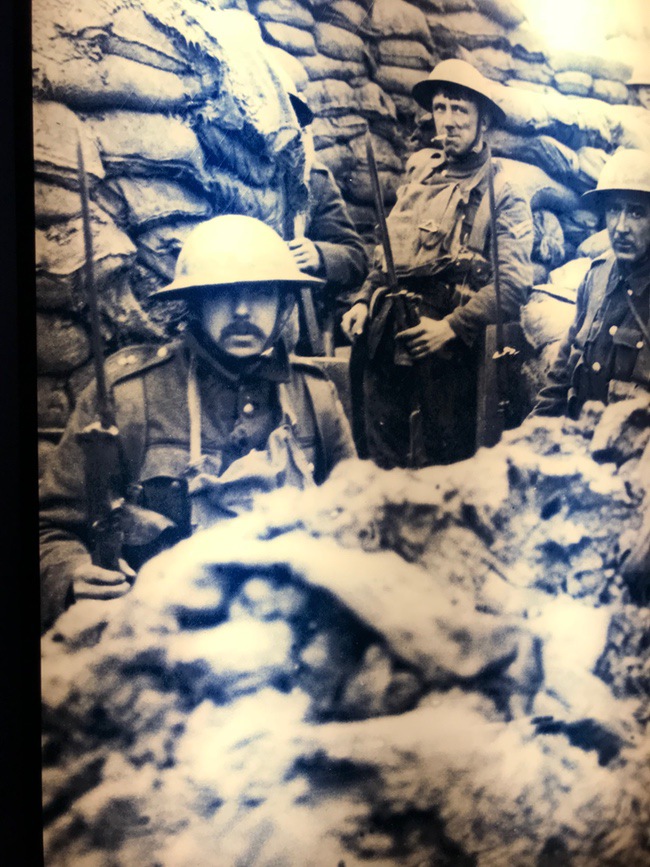

Throughout the museum, photographs tell a story of hardships encountered. Trench life can be seen and even felt, in a real life-sized trench that you can enter.

Throughout the museum, photographs tell a story of hardships encountered. Trench life can be seen and even felt, in a real life-sized trench that you can enter.

Sometimes the little things tell the big story. These are fragments from Reims Cathedral in France, built in the 14th century and bombed by the Germans. These remnants were salvaged and later presented, in 1926, by the French ambassador to the Liberty Memorial as a gift.

Who hasn’t heard of a doughboy helmet? Here’s one on display. Supposedly, when US troops arrived in Paris, the French called them “Teddies,” which General Pershing did not like. Other nicknames were proposed and “doughboy” stuck. It has its origins in 1846 in Texas during the Mexican-American War, when troops marched while covered in chalk dust, and were called “adobes.” That transitioned into “doughboys.”

While on the topic of Gen. Pershing, a Missouri native, in May 1917, he was appointed as commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces, which gave him command over the land forces of US military in Continental Europe and in the UK.

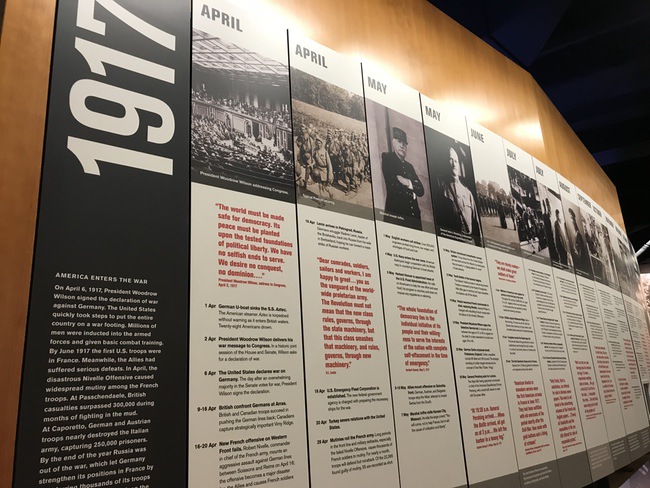

Here’s an example of why it will take days, not hours, to tour this place. This is the timeline laid out for after the US joined the Great War.

What provokes a nation to go to war? Take a look at this chart.

Meanwhile, back in the US … after the Germans sank the Lusitania, this poster from 1915 motivated young men to volunteer for the services.

After the US entered the war, posters created by American artists, recruiting volunteers, popped up everywhere. Can you spot the most popular one? It’s a self-portrait done by artist James Montgomery Flagg, aka Uncle Sam.

In this display case, you’ll see a collection of knives and grenades.

Look who made the Ace Hall of Fame? A name that became hated in WWII, Hermann Goering.

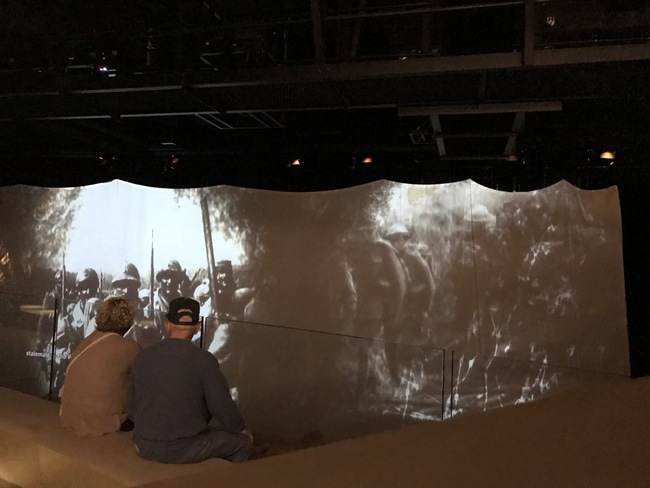

You can sit for a while and watch a video with surround sound. It takes you to the battlefield.

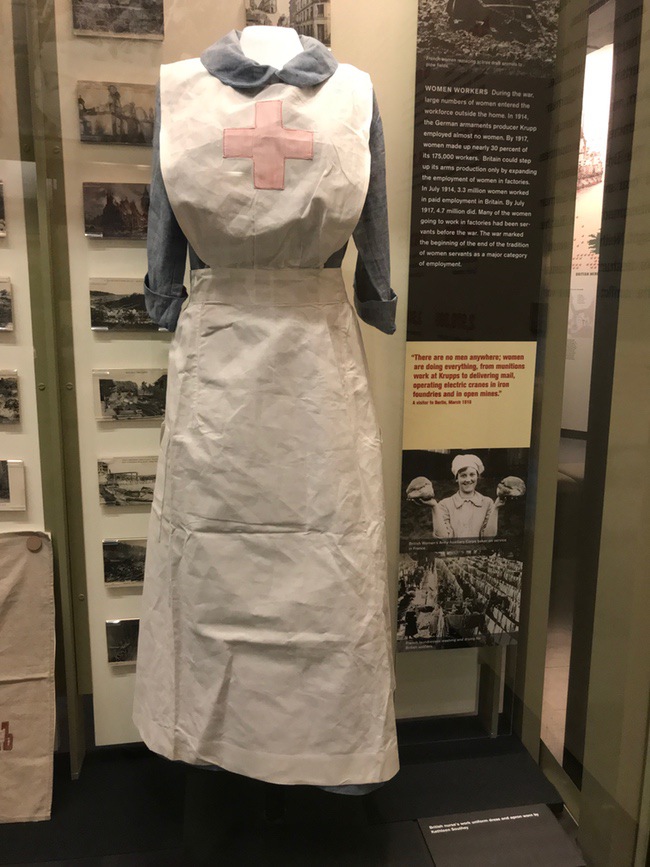

The museum is arranged chronologically, and I have to admit, I spent most of my time in the US section. It’s been said that angels wore these uniforms, as they tended to the injured.

It’s been said that angels wore these uniforms, as they tended to the injured.

No doubt you could stand and read and soak it all in from this display case, which features weapons and history about the Choctaw code talkers, from Oklahoma.

The poem “In Flanders Fields” evokes imagery that surrounds WW1, and Kansas City artist Ada Koch created “Reflections of Hope: Armistice 1918,” in the reflecting pool in front of the main entrance. Each poppy is different and the 117 poppies each represent 1,000 American lives lost in the war.

For current exhibits, commemorations and events, visit the National WWI Museum and Memorial online.