This is the second part of a two-part series on the life of Dr. Richard Bullock, originally written in 2003. At that time, Dr. Bullock held the Robert H. Quenon Chair of Mining Engineering at UMR. Dr. Bullock’s life journey took him from being an Ozarks boy to a worldly mining engineer, culminating in an endowed professorship at a prestigious mining university. This part begins when Bullock sets out to see the world, as a newly minted mining engineer, in 1951.

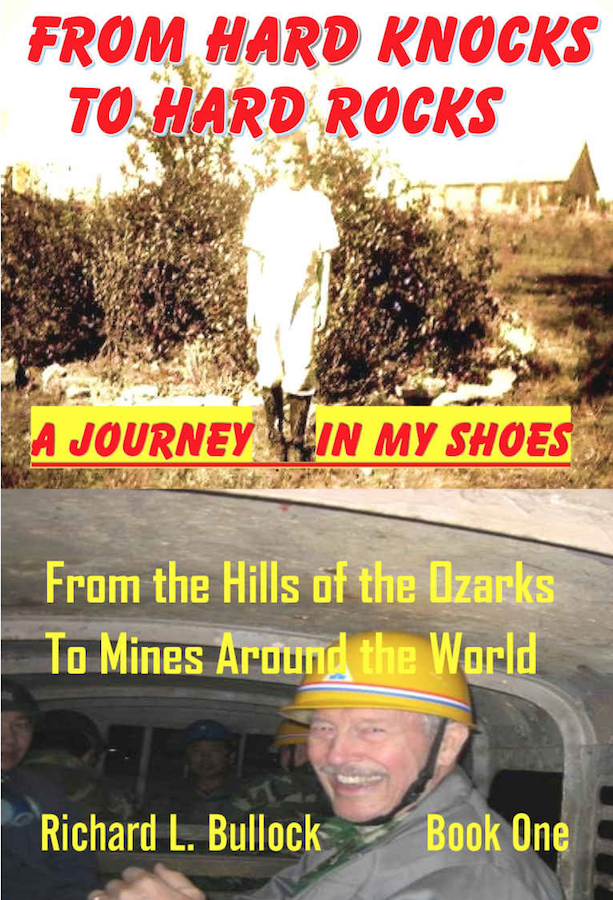

It would take a thick book to relate most of Dr. Richard Bullock’s experiences, and fortunately, he is in the process of writing one. Tentatively titled “A Journey in My Shoes,” it is filled with action, adventure and some very tender moments. For although Bullock had many triumphs in his career, his personal life had tragedies – including the death of a child and three failed marriages.

Richard Bullock’s Memoirs, Part 2

Back when Bullock graduated from the Missouri School of Mines, he could not afford a car, so he took a train and then a bus, to get to the mine site in Colorado, the location of his first job. He recalled, The bus pulled over and let me out When I looked to see what was ahead, there was this tiny village of Gilman perched precariously on the side of this rugged Battle Mountain at 9000 feet.

Bullock soon settled in, living in bachelor’s quarters. He immediately became a check surveyor, which meant he had to make sure that the development tunnels that were being driven from the Eagle Mine would correctly intersect other old nearby abandoned mines.

At least he worked above ground most of the time that first summer. He recalled that the Eagle Mine employed mostly Mexican miners – men he holds the highest respect for, since they toiled in hot stopes [underground workings], using handheld jackhammer drills and dynamite. Although ventilated, the stopes registered more than 120 degrees.

He married his high school sweetheart, Jackie Leavitt, and was just settling into the routine of married life when in 1952, during the Korean Conflict, Uncle Sam called. Jackie came home to Missouri and Bullock went through basic training in Kansas.

After training, he was posted to Ft. Belvoir, just outside of Washington, D.C., as an instructor at the Engineer School, where he taught classes on pit and quarry operations and explosives. He also started writing – something he has continued to do over the years, including several collegiate textbooks on aspects of mining.

After training, he was posted to Ft. Belvoir, just outside of Washington, D.C., as an instructor at the Engineer School, where he taught classes on pit and quarry operations and explosives. He also started writing – something he has continued to do over the years, including several collegiate textbooks on aspects of mining.

In 1954, Bullock came out of the army and back into the trenches at MSM, this time to get his Master’s degree. Upon completion, he had ten job offers. Bullock took a job with St. Joseph Lead Company, near Bonne Terre, Mo. While there for ten years, Bullock was part of Missouri mining history -the shift from the Old Lead Belt to the New Lead Belt- working in research and development, and also mine supervision. While there, he made many changes in mining techniques and says, Since that time, probably 40-50 million tons of rock have been broken using the blasting system I developed.

While with St. Joe, Bullock not only helped to bring all the Viburnum and Fletcher mines up to full production, he also served the community. The company hired an urban architect to develop the town, but it took Bullock and other mining people to fight for a high school in Viburnum. He was also instrumental in establishing the first bank and served on its Board of Directors. During this time, he also earned the first Doctor of Engineering Degree from the University of Missouri system from MSM/UMR.

While with St. Joe, Bullock not only helped to bring all the Viburnum and Fletcher mines up to full production, he also served the community. The company hired an urban architect to develop the town, but it took Bullock and other mining people to fight for a high school in Viburnum. He was also instrumental in establishing the first bank and served on its Board of Directors. During this time, he also earned the first Doctor of Engineering Degree from the University of Missouri system from MSM/UMR.

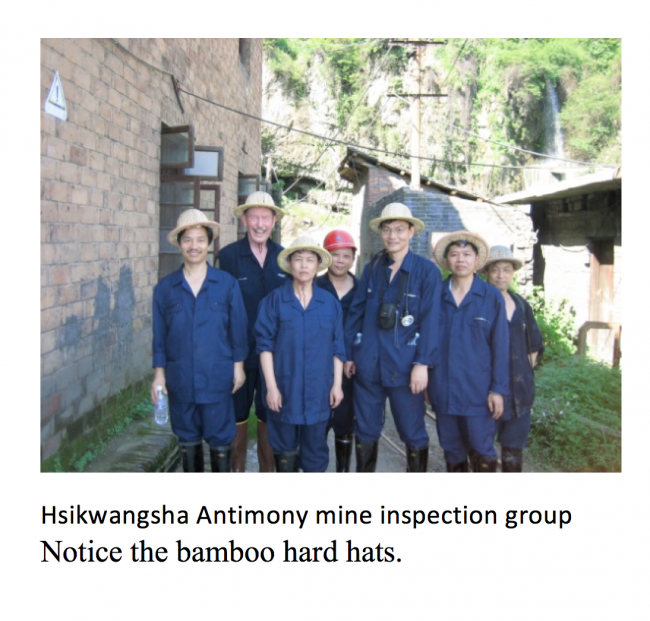

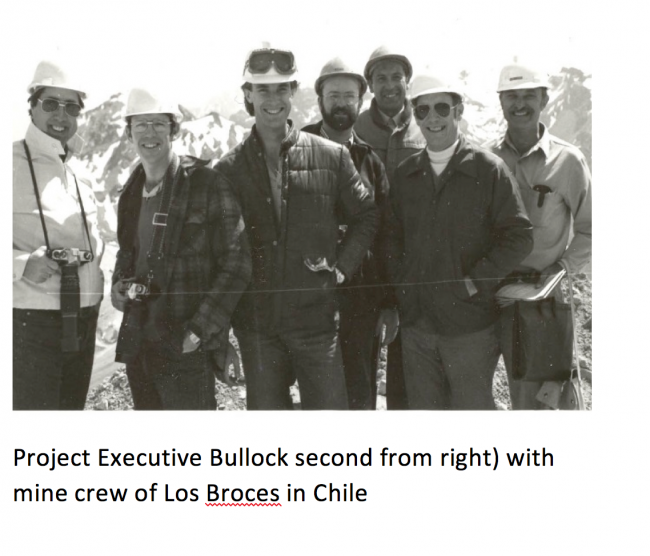

After working for ten years in the New Lead Belt, Bullock accepted a corporate job with the company in New York. Later, he went on to work for Exxon, evaluating major mining properties in North and South America, Australia and Europe. Exxon issued him an extensive wardrobe – with apparel equipped for everything from tropic to arctic conditions. He even visited a mine near the North Pole.

After working for ten years in the New Lead Belt, Bullock accepted a corporate job with the company in New York. Later, he went on to work for Exxon, evaluating major mining properties in North and South America, Australia and Europe. Exxon issued him an extensive wardrobe – with apparel equipped for everything from tropic to arctic conditions. He even visited a mine near the North Pole.

About his first trip to Peru, he recalls, The most impressive thing was seeing the Peruvian Andes people and the conditions they live in. It was really shocking to me, and I’ll never forget seeing a little Peruvian boy out tending his llamas in a mountain pasture at about 10,000 feet; he was as glassy-eyed as any child could possibly be, because he was probably doped up on coca or the beer they drink. He was standing there, barefoot in the snow.

About his first trip to Peru, he recalls, The most impressive thing was seeing the Peruvian Andes people and the conditions they live in. It was really shocking to me, and I’ll never forget seeing a little Peruvian boy out tending his llamas in a mountain pasture at about 10,000 feet; he was as glassy-eyed as any child could possibly be, because he was probably doped up on coca or the beer they drink. He was standing there, barefoot in the snow.

Throughout the years, Bullock’s career took him to 19 foreign countries, including visits to coal mines in the United Kingdom and Germany. Several years, he traveled more than 200,000 miles.

And now? After seven years of mentoring and teaching two new courses at UMR that he developed, he says, It’s time.

He and his wife, Jan, plan on retiring somewhere in the Northwest. Meanwhile, UMR will still receive the benefits of Bullock’s experiences, as he will continue to teach online courses.

Bullock leaves knowing that mining is a safer, mechanized/automated industry and that mining engineers today have greater opportunities than he once had, and that it’s still possible to become a mining engineer and see the world. He says, On the other hand, you can still have a good career in mining and never travel a lot. He added, It’s a glamorous lifestyle, but not a glamorous career. In fact, he says, The opportunities for mining engineers are even greater than they were before, especially now that we have many quarries hiring mining engineers.

Dr. Bullock has written a 2-part book titled “From Hard Knocks to Hard Rocks: A Journey in My Shoes.” Available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Read the release about his books.

Read part 1 of Dr. Bullock’s memoirs, as told to me in 2003. Part 2 will be available in early 2019.