On a recent trip to Lebanon, Missouri, I swung by the Route 66 Museum and Research Center, located in the city’s library complex, the Lebanon-Laclede County Library. I had visited the museum several years ago, and wanted a refresher.

Lebanon fought hard back in the day to get this iconic road that it knew would bring travelers through and dollars spent. In 1922, when the State Highway Commission announced it wanted to create a new highway across the Ozarks, the folks in Lebanon wanted in.

So, they started going up to Jefferson City and made noise. They even, according to an About Lebanon website, brought the local high school band to add to the noise. Politicians had been rumored to say that there lay too many hills and rivers to traverse if putting the new road through Lebanon. Some of Lebanon’s influential leaders met with the state’s engineers and pointed out the path that would be the least cumbersome.

Originally thought to be named Highway 60, in 1925 politics came into play for eventually reaching the number “66.” The state of Kentucky agreed to allow Springfield to have the number 60 if the city agreed to connect Kentucky’s highway to its area. Cyrus Avery, a businessman from Tulsa, had been negotiating for the tourist laden road for the Ozarks. Satisfied with the results during the negotiations, Kentucky officials suggested that the road be named Highway 62. Avery didn’t like that number, and wanted to use Route 66 to connect the new high system that ran from Chicago to Los Angeles.

You can find out all this information and more, and also, discover where historic places can be found in the area – just by visiting here.

There’s also a research area available, so that students, history buffs and authors can find information pertaining to the construction and development of this road.

Pics from the Route 66 Museum and Research Center

Want to step back into a Mayberry RFD-type time where gas stations symbolized so much more than a quick stop for gas, restrooms and junk food? A 1950’s-style gas station exhibits the complete set-up for your imagination.

The Munger Moss Motel still stands and serves to this day. This switchboard found its way over to the museum.

Check out this roadside tourist cabin, typically, as the sign reads, found in court-like settings.

Recently, I have been collecting Ozark “tourist pottery” or “roadside pottery.” Made in the Hollister area in the 1930s and a little later, it is a concrete-based pottery that features swirls. The museum exhibits a fine collection and even heralds an article in “National Geographic,” done in 1943, about this type of pottery. You could pick it up for very little money back in the day, from roadside vendors. Today, it’s a different story.

It’s all in there … this display features life as a motorist in the late 1920s and early 1930s along this stretch.

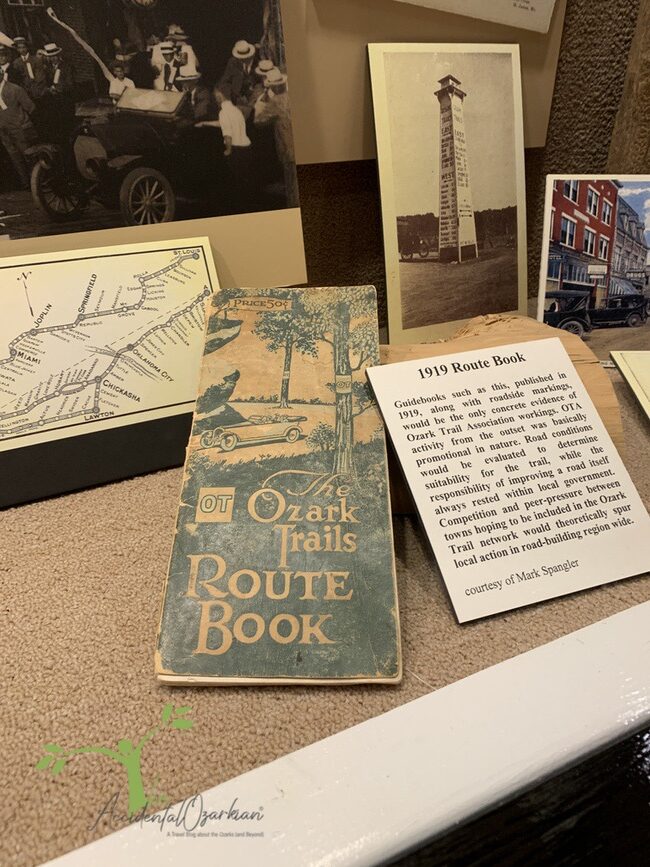

There are some serious treasures in the display cases here, including this old book highlighting Ozark trails.

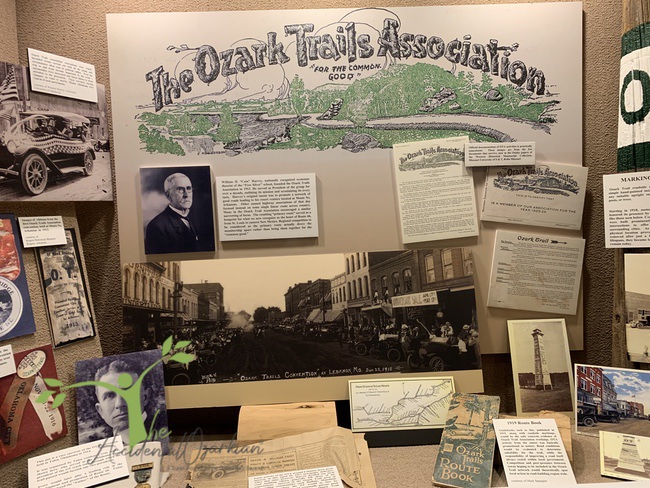

Ever heard of The Ozark Trails Association? It proves that even back in the day, states and business leaders recognized the importance of tourism. Founded in 1913, the association focused on Route 66, to its demise.

The Kinderhook Treasures Gift Shop is located near the museum entrance and features several locally made items from craftsmen and artisans. I purchased a book by folklorist Vance Randolph and a lovely pair of scrimshaw earrings featuring dragonflies, done by artist Michelle “Mike” Ochonicky, from Stone Hollow Studio.

How to Get There

People traveled on Route 66 from 1926 until December 1957. You may visit the museum located at 915 South Jefferson Avenue. Hours are Monday through Thursday, 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., and Friday and Saturday, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission is free. Closed on Sundays. Visit the Route 66 Museum and Research Center online for more information.