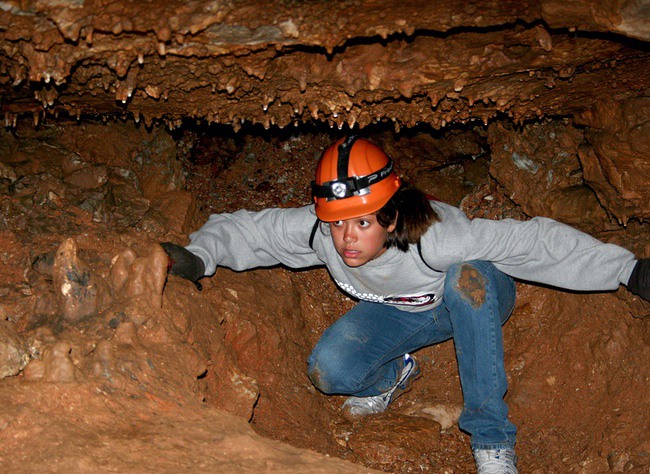

I love this story from a few years ago, when we went “wild caving” in the Ozarks with a bunch of teenagers. ~BB

“Whoa!” laughed Alec as his 6-foot frame sunk up to his knees in cave muck. “This is cool.” Too late to turn back, our crew of cavers had entered the mudroom of Mushroom Cave. So we slogged on, determined to find the end of the passage. Meanwhile, the mud sucked 10-year-old Valerie’s shoe right off, and her aunt had to go digging to find it.

“Hey, look – a salamander,” cried Brandi, as she pointed her headlight at an orange creature lying in a little puddle on a side bank. “Watch your step,” she admonished us, as we hauled ourselves up out of the mud and onto a natural walkway near the salamander – like hoisting ourselves out of a pool, but with a lot of suction involved on the downside.

“Now it’s time to look up,” said our cave guide as we entered the back room. Bats hung from the ceiling, seemingly oblivious to the intruders into their world.

Wild Caving

Caves come in all shapes and sizes, but only 2 categories – domestic and wild. On this day, we had entered the world of the wild cave, a permit cave in Missouri where rules must be followed and attention to detail must be practiced.

Although wild caving is practiced worldwide, cavers often are a secretive lot. Although they will most likely be happy to guide the novice who is interested in caving, they will not announce to the world where the cave is located – like the turkey hunter who does not give away his secret hunting spot, or the trout fisherman who knows of a little hidey hole on a special stream.

Cavers usually belong to “grottos” – groups who like to explore caves. Sometimes these grottos will map new caves. Two hundred grottos associate themselves with the National Speleological Society (NSS), which encourages its 12,000 members to conserve and protect caves and also promotes safe caving.

Caving is not only about recreation, it’s about research, too. Caves are studied for the following reasons – archaeology, ecology, biology, cartography, history, geology, mineralogy and hydrology. Cavers also learn mapping techniques; possibly, some of the only unmapped places left on earth are in caves.

If you find something unusual while caving, leave it where it is and take several photos of it, placing a coin or a finger beside it so that the scale of the item can be measured. Make a note of where it is on the cave map, or draw a map. Take the photos to the park authorities or to a nearby college science or history department.

According to Missouri geologist/caver Jo Schaper, “ Much of the value of an artifact is destroyed if it is moved. If something is lying in plain sight where it might be removed by a cave vandal, it might be appropriate to hide it somehow (cover it with a rock), but don’t disturb the area if you can help it.”

In order to be effective, caving must be safe. Even a day trip to a local wild cave must be fully planned for, and if permits are required, they must be acquired. Calling ahead to talk to park authorities pays off, or arranging to accompany a grotto to a site will work, too.

Safe cavers take care to dress for the temperatures in caves, which can vary from the high 70s in the Southwest to the low 40s in the North. They also ascertain whether or not the cave will be wet or dry.

Starting with underwear, cavers usually choose the type such as hunters wear – polypro or silk. Socks should be layered, too, with a pair of moisture resistant socks and then, wool or polypro socks. Layers of moisture-repellant clothing, followed by kneepads, sturdy boots or rubber boots and a lighted helmet complete the uniform.

Schaper says, “Cavers are deliberately getting wet, so they know they want warmest stuff when wet next to most of their skin In dry caves, you don’t want to bulk up with a zillion layers, because you will also be crawling, stooping, scooting and otherwise sweating.”

She continues, “If you will be immersed all day, it’s usually 100% polypro under a 1/8 inch neoprene wetsuit, then a coverall.”

Gloves not only protect your hands, but also protect the delicate cave surfaces from the natural oils in your hands.

A backpack is an essential piece of caving gear, carrying a host of essential equipment for exploration, and possibly survival.

After the cave expedition, it is a good idea to have a towel and a fresh change of clothes and shoes handy outside. Trash bags work well for keeping muddy items separated from other items.

After spending time in a cave, be prepared to come away with a whole new perspective. After all, when you have seen what is going on underground, your eyes will be opened to the beauty of the underground ecosystem.

Remember to follow the cavers’ rule, “Take nothing but pictures. Leave nothing but footprints. Kill nothing but time.”

CAVING CAN BE DANGEROUS IF ATTEMPTED WITHOUT PROPER GEAR AND KNOWLEDGE.

- Check-in at the visitors’ center at a park so they can tell you which caves are open or closed. Some closed caves can net you a $50,000 fine if you are in them the wrong time of year.

- Rule of Threes: Take 3 people minimum. Take 3 sources of light each. (One should be mounted on a helmet or hardhat, and one light should also serve as a source of heat.)

- Always tell someone not on the trip where you going, when you will return and who to call if you are two or more hours overdue.

For more information on caving, visit the National Speleological Society at www.caves.org.

WHAT’S IN A CAVER’S PACK?

According to caver Jo Schaper, “Your pack will vary depending on the length of the trip, what you are going to do (survey, photography, explore) and the conditions of the cave and the weather outside. Leave enough room in your pack for a warm when wet shirt or sweater, and put on/take off as needed.”

- Rope or 25 feet of one-inch wide webbing (for a handline)

- One liter of water

- Non-crumbly snack food, such as energy bars or cereal bars

- Extra batteries for flashlights

- 2 Mini-Mag flashlights

- Second helmet-mountable light

- “Rite in the Rain” notebook, stubby pencil

- Camera

- Batteries and bulbs for main light and backup lights, plus one set of spare batteries for each light

- Clean handkerchief in plastic bag

- Remember a butane lighter if using a candle

- Big black trash bag (large enough to wear as a heat tent)

- Spare cotton gloves with plastic palm nubbies

- Aspirin/Ace bandage/antibiotic ointment/bandaids wrapped in plastic bags.

- Safety pins

- 10-feet-length of duct tape, wrapped around itself

- Tiny multi-tool and small pocketknife

- Camera

- Cave map (or map to the cave) if available. It’s a good idea to photocopy the cave map and leave a copy with your parents and friends, too.

- Carbide light or candle (Bring butane lighter)

THERE ARE NO PORTA-POTTIES IN CAVES

Cavers never leave anything behind. The cool temperature of the cave preserves everything. Trash, food or human waste can poison the ecosystem for years.

Most cavers carry a wide-mouth polyethylene bottle for urine, and toweling, plastic wrap, aluminum and plastic bags for cave burritos – solid waste.

For overnight expeditions, cavers carry a small kitty litter box or a slop bucket. Hi-tech disposal products, such as gelling agents, help control the waste problem. But whatever you use, the waste must be removed from the cave and disposed of properly.