A friend called me and asked me if I’d like to go to the “Poor Farm.” She mentioned that her neighbors had purchased the site where the Wright County Farm and Alms House used to stand, and would be willing to show me where the graveyard associated with it lay.

How could I say no?

We headed over to where Bob and Debbie Ziy live, where Debbie greeted us and invited us in for homemade German chocolate cake, and fresh brewed iced tea. Bob came in, joined us at the kitchen table and took an afternoon break from mowing.

Bob grew up in the Bootheel, in Parma, Missouri. He worked for Caterpillar in Peoria, Illinois, and in 1976, he came over to help a friend do some seeding in this area. He saw the farm for sale and fell in love with it. His house sits on a hill with sweeping vistas, and pastoral views.

He said he made an offer and signed the paperwork on Easter weekend. In 1992, he had the second house torn down (built in 1943 and not to the grand scale of the original Poor Farm residence) so that he could build his new house, but said, “I left the front end of that old basement under the front porch.” The old basement had three-foot thick walls, and the prior owners had used it when they rebuilt in 1943. Bob laughed and said that they’d never felt spooked and didn’t feel as though the site was haunted.

History of the Wright County Farm and Alms House

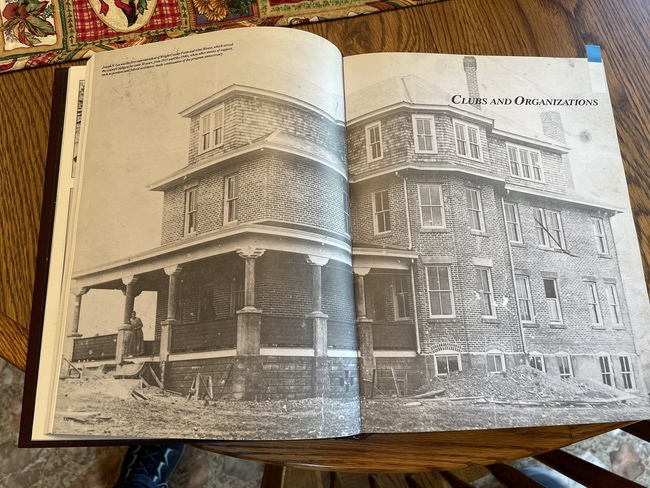

The Wright County Farm and Alms House, aka “Poor Farm,” was built in 1915 and lasted until about 1942, when a fire destroyed the entire place.

We took a ride out in the pasture to where Bob said he found the graves, that had been decimated somewhat by cattle grazing in the same area. He seemed incensed that people had allowed the graveyard to be overrun by cattle and said it’s one of the first things he did after acquiring the property – to fence in the graveyard. “It just ain’t right,” he kept saying, in regard to allowing cattle to destroy a consecrated ground.

Bob reckoned there were at least 12 flint grave markers onsite from residents of the Poor Farm, but he thought there might be more graves, especially since there are depressions in the soil. A resource at MoGenWeb stated that there should be 27 death certificates associated with the cemetery, but it may be that it was an existing cemetery even before the Poor Farm started burying its dead there.

Bob said he remembered a friend telling him that about a relative who lived there who requested that he not be “buried out back in the woods, but in town.” He also said the original road ran along the fence line that skirts the north side of the farm, which is near Hartville, Missouri.

More about ‘Poor Farms’

Although Poor Farms might have been a way for society back in the day to “take care” of indigent and mentally ill people, these places have been reported to be centers of cruelty. According to James Whalen, in a publication based in New Brunswick, “While all types of poor people were given shelter in almshouses, the purpose of the workhouse was very particular. As Bill Wister, in ‘Poor Law Legislation in New Brunswick,’ put it:

‘The Work Houses were seen as a method of controlling the outdoor relief [welfare] and providing a deterrent to those wanting relief from the parish. Also the Work House was seen as a response to the idle and drunk.’”

Housing men and women together, some with a criminal backgrounds and mental illnesses combined, the farms couldn’t have been centers of joy and happiness. Often it’s surmised that people took their relatives that they couldn’t take care of to these places, dropped them off and said goodbye.

Bob said he heard that this location grew its own vegetables, some fruit and raised a hog or steer.

All in all, it sounds miserable, even though it stood on a beautiful site. There’s nothing left to see except a few flint markers, which lie tucked away on private property.