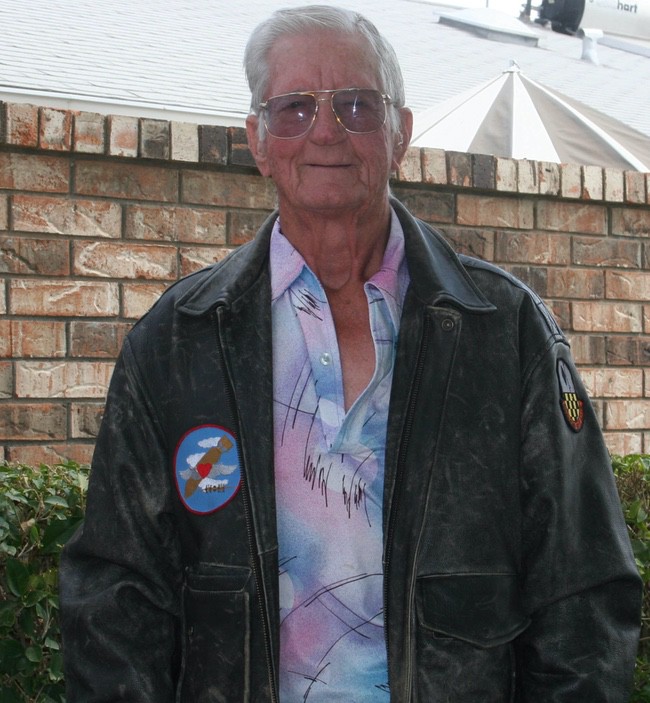

I met Marvin Guthrie in the spring of 2007. He lived down the street from my parents in Arizona. They told me he had a story to tell. Little did I know … If you’ve ever watched reruns of “Hogan’s Heroes,” you’ll see some similarities.

Throughout the years, I have been honored to interview men who served our country during WWII. It seems you cannot visit a nursing home or a senior citizens’ community without meeting one of these brave souls. Yet, their time on earth wanes – an average of 1500 WWII vets die daily – and most of the ones who are still alive are in their 80s.

Marvin Guthrie lives down the street from my parents in Sun City West, Ariz., and I caught him between golf games and homeowner association responsibilities for a talk about his life as a prisoner of war in a stalag during WWII – quite a bit different than the scenes from the popular TV show, “Hogan’s Heroes,” but in some ways, the same.

Guthrie volunteered for active duty in Kansas on November 19, 1943. For a guy who hadn’t seen much of the country, his adventures had just begun. He started in Texas, where it became apparent that he was meant to be a gunner. He then went to Mississippi, followed by training in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico and California. At most of these places, he received very little training in gunnery techniques for a B-24. He says, “The B-17 got all the advertising in the news, and they called it the ‘Flying Fortress,’ yet we could carry twice the bomb load that they could and fly faster.”

He then went to Oklahoma, Kansas, and on to Virginia. By March 1944, he was somewhat trained to travel to the air base in Italy where he would work with his crew in the 459th Bombardment Group. The crew then flew from Florida to Brazil to West Africa then Morocco, Tunisia – where they took a three-day break because of weather – and then on to their base at Giulia Field in Italy. Finally, he had some on-the-job training as the ball turret gunner on 12-16 hour missions. “It was especially tiring for me.” Guthrie’s position required him to lie on his back with his knees up. He said, “If you got hit hard with flak, the chances of getting out of it and into a parachute were practically nil.”

Each crew had to fly 50 missions before they could go home. On the 25th mission, the crew would get some down time, maybe on a nearby beach. Something in the back of Guthrie’s mind nagged him and he mentioned to the pilot that he never wanted to have to fly to Munich. He said, “We never flew there until the 24th mission, and that’s when we were shot down.”

Becoming a WW2 POW

On the morning of June 9, 1944 – Guthrie’s mother’s birthday – the crew flew a mission to bomb the Alteruhofen Ordnance Depot near Munich. They were the “tail-end Charlie,” the last plane, and therefore the lowest in the formation at 22,000 feet. The crew saw an escort, which they assumed was a U.S. P-47, but instead was a Focke-Wulf. The German pilot flew up alongside the left side of the plane, saluted the U.S. pilot, executed a split-S turn and left. Then, the strafing began near Liens, Austria. The Germans knocked out the #1 engine and the #3 engine sputtered. One of the gunners was hit with shrapnel, and Guthrie injected him with morphine so that he could make it to the ground.

“Fortunately, there happened to be a big valley, with mountains behind us and mountains ahead of us,” said Guthrie. Guthrie noticed that the waste gunner’s parachute was smoking, but the young man still bailed out. His parachute never opened and the man died instantly. Guthrie says he was the last one out of the plane and the first one on the ground. It was the first and last time he ever jumped from a plane. The plane went into a sideslip and crashed shortly after Guthrie exited.

Within minutes, a member of the home guard appeared with a rifle. Guthrie said, “I could have killed him three or four times, because he walked in front of me and I had my .45 and all my stuff hidden under my parachute.” He decided against killing the guard on the spot.

When German soldiers appeared, they discovered that Guthrie had his weapon – which they confiscated. After spending two days in the local jail, the crew was then placed in solitary confinement near Frankfurt. About the interrogators, Guthrie chuckled and said, “They knew more about things than I did. They’d tell us, ‘We can shoot you as a spy.’ We’d just laugh at them, that’s the only thing you could do.” Guthrie surmises that the guards didn’t rough him up because he looked Aryan, with blonde hair and blue eyes. The Jewish and Jewish-looking soldiers were treated far worse.

Just Like ‘Hogan’s Heroes’

After receiving suitcases furnished by the Red Cross, the crew took a train ride to a gulag. Here’s where the reference to “Hogan’s Heroes” comes in – some of the prisoners had been radio operators. According to Guthrie, they wired together homemade radios from razor blades, wires and other accoutrements. The men listened surreptitiously to the BBC everyday and realized that D-Day had been a success. They decided to bide their time while the U.S. and its allies won the war. Guthrie learned to play bridge well, because according to the rules of the Geneva Convention, enlisted officers were not allowed to work. He said, “I could see then that this was the easiest way to pass the time – it takes total concentration to play bridge.”

Sixteen men in one room received a gallon pail of boiled turnips or potatoes to share per day, along with a quarter of a loaf of bread each for the week. According to Guthrie, a full loaf weighed six pounds. Guthrie lost 30 pounds, and looked forward to receiving part of a Red Cross parcel occasionally. He said, “There were five packs of cigarettes in there, and you could trade your cigarettes and get more for them than for anything.” Guthrie quit smoking, saying, “I’d rather have the food than the cigarettes.”

The prisoners slept on gunnysacks filled with excelsior [wood wool] and only bathed once a month. Sometimes, they suffered from lice infestation.

In September 1944, the Germans moved another camp to Guthrie’s, which added six more men to the room, and that meant fewer potatoes from the pot for the men. Guthrie spent his confinement in Stalag 4 and then Stalag 1, which held about 4500. He could send one letter per month, and he received two form letters from his mother.

Freedom

Guthrie remembers being liberated on May 1, 1945, after the Germans left the camp. The men were left alone in the camp, waiting for the Russians to show up. When a Russian general arrived on the scene, he gave orders for all to prepared to march into Russia. He says, “We happened to have a full-bird colonel who knew all the ins and outs of politics, and he told the Russian general, ‘You go straight to hell, because we’re not going there.’”

Guthrie saw a concentration camp, while marching to be airlifted back to France. He said, “Those people were nothing but skin and bones.”

Guthrie and his crew reunited one time in the early ’90s. In 2000, Guthrie returned to Austria and visited the crash site, where he found some of the plane’s skin. Local residents gave him some other pieces from the plane. Now, 86-year-old Guthrie is the only member left.

We should remember to use the time that these veterans have left not only to honor them for their service, but also to listen to their stories so that we never forget them.

WWII by the numbers

- 16.1 million – number of U.S. armed forces personnel who served in World War II between Dec. 1, 1941, and Dec. 31, 1946

- 33 months – the average length of active duty by WWII personnel

- 73 percent – number of U.S. military who served abroad

- 16 months – average number of months of service abroad

- 292,000 – casualties of U.S. soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines killed in battle in WWII

- 114,000 – number of other deaths sustained by U.S. forces

- 671,000 – number of U.S. troops wounded during WWII