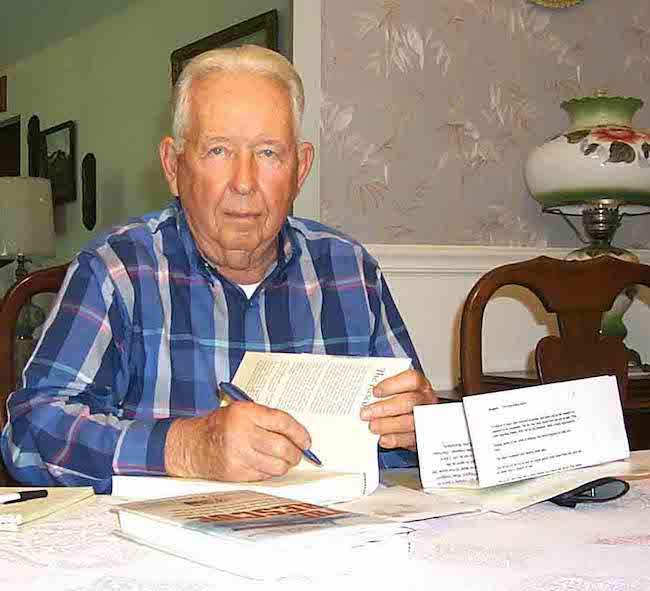

Harry S Truman said, “Study men, not historians.” When Howard Chrisco of St. James looks back at the escape that he and his fellow soldiers made from a Japanese work camp in the Philippines during WWII, he cannot help but think that there were too many “coincidences” to make the smooth transition from captivity to freedom. He likes to think that the Almighty had a hand in the ordeal.

In 1941 when Chrisco was 21-years old, he enlisted in the service and was assigned to the 79th Coast Artillery at Fort Bliss Texas. Shortly after training, Chrisco was sent to Clark Field in the Philippines.

In April 1942, troops at Clark suffered constant attack from the Japanese, causing the commanding officer of the U.S. troops to surrender. Chrisco began the adventure, or some would say nightmare, of his life.

He was forced to drive for the Japanese during the Bataan Death March. Then he and nine other POWs worked in a motorpool/garage as mechanics and truck drivers. After a year in confinement and after being slapped around, beaten and misused, the men planned their escape. One of their crewmembers had already escaped and found a safe place with the guerillas.

The Escape

One afternoon while playing cards, the Americans who were in the motorpool (two of the men were offsite in Murcia, leaving the seven who later dubbed themselves “the lucky seven”) – Chrisco, Russell Snell, Jim Dyer, Dick Jenson, Floyd Reynolds, Irving Joseph and Bob Young – decided the time was right to escape, since most of the guards were off celebrating.

Chrisco ran and grabbed three rifles and 76 rounds of ammunition and the men prepared to leave in a truck. Before the crew left the garage, they heard and saw a band of Japanese soldiers merrily chanting a victory song while coming down the street. Just when the Americans thought their plan for escape had evaporated, the soldiers turned a corner and marched off.

When the POWs started to back out of the garage, a truckload of armed Filipino Bureau of Constabulary troops pulled over and parked in front of the garrison across the street.

Finally the Captain of the BC troops left the building and climbed back into his truck, not noticing the anxious looks on the seven men’s faces across the street.

The captives were about to leave the premises when a guard nicknamed “Blockhead” men returned from his bath. Two of the POWs went over to Blockhead and asked for a match. Chrisco picked up a pipe, hoping that he wouldn’t have to use it on Blockhead’s head. Instead, he explained to Blockhead that the men were going to move one truck from the garage into the street and bring another truck in.

The men climbed into the get-a-way truck and on the way out, the driver sideswiped the door. Chrisco recalls, “We just got down the street about 200 yards and here comes the Captain and the Sergeant back from the club. See, we just about got near getting caught all the time.”

The escapees headed toward the center of town, where the Spanish would often have parties in the evening. Chrisco says, “When we turned the corner near the park, here came a little pony and a cart, and he [Jensen, the driver] cut it short and we ran over a curb. I thought he was going to dump us right there in the middle of town.”

The next obstacle was the guard shack near the pier, where the Filipino guards just waved at them. The men anticipated having to meet a Japanese guard closer to the pier, but that guard was occupied using the phone.

Looking back on the escape, Chrisco says, “So many things worked in our advantage there to get away, and it’s hard to believe that it all came together like that and we didn’t have to fire a shot.”

Chrisco found Filipino guides to take him and his buddies to find the anti-Japanese guerillas. He recalls, “We were wishing for rain, and it was just pouring down that night. There wasn’t much moonlight.” In other words, it was a perfect night to escape.

Chrisco found Filipino guides to take him and his buddies to find the anti-Japanese guerillas. He recalls, “We were wishing for rain, and it was just pouring down that night. There wasn’t much moonlight.” In other words, it was a perfect night to escape.

Of the Lucky Seven, only Chrisco chose to fight with the guerillas before being wounded in an ambush. After 10 months the crew was ordered to report to the evacuation post near the Barrio Basay dubbed “Shangri-la.” The American submarine, the Crevalle, picked them up, along with 34 other refugees.

Chrisco recalls the few times that the Japanese Navy nearly found the Crevalle. “In the submarine, we were under attack for probably three-four hours. They came dragging for us and we could hear the cable hitting the side of the sub.” The submarine sustained damage from depth charges, yet slowly made its way to Australia.

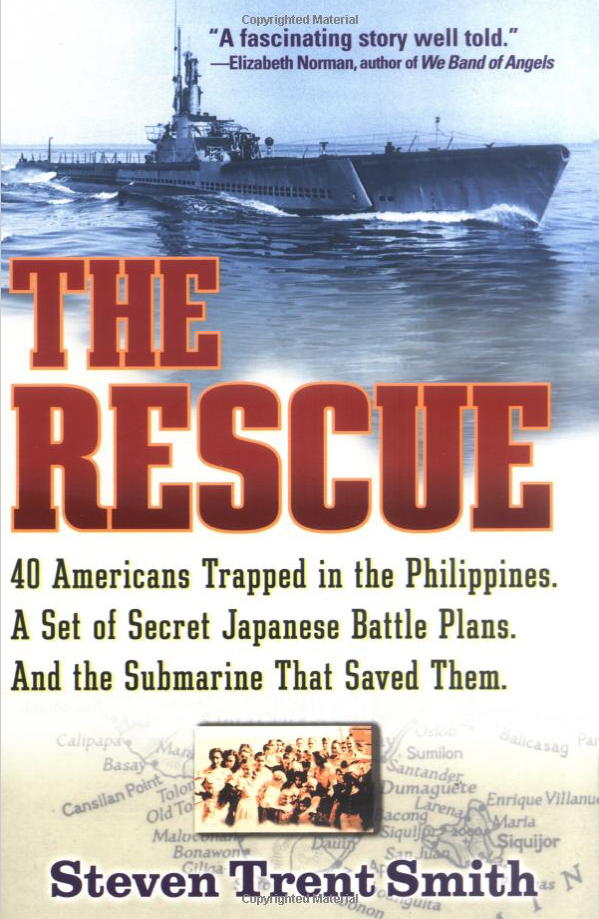

‘The Rescue’

Steven Trent Smith tells the story of Chrisco’s ordeal in the book “The Rescue.” Chrisco’s philosophy on leadership has been featured in Col. Jimmie Dean Coy’s book titled “A Gathering of Eagles,” and his spiritual resilience will be highlighted in a forthcoming book by Col. Coy.

Steven Trent Smith tells the story of Chrisco’s ordeal in the book “The Rescue.” Chrisco’s philosophy on leadership has been featured in Col. Jimmie Dean Coy’s book titled “A Gathering of Eagles,” and his spiritual resilience will be highlighted in a forthcoming book by Col. Coy.

A documentary featuring “The Rescue” aired in May 2005 on the History Channel.

Now retired, Chrisco works tirelessly preserving memories and giving accounts of his time in service during WWII. He speaks to students and groups about his experiences, and not a day goes by that he does not think about the ordeal.

Chrisco belongs to the American Ex-Prisoner of War Association, and served as district commander of a unit based in West Plains.

From his war experience, Chrisco believes there are three ideals everyone ought to live by: always do what’s right; character and integrity are important; and be honest – your word is your bond.

From someone who has “been there,” Chrisco’s words make him a living history book – the type of man that Truman would more than likely use as an example to illustrate his point.

First published in May 2005 in the St. James Leader-Journal.